This article was originally published on LinkedIn.

Imagine this: a generous benefactor approaches you with a staggering $50 million donation for your foundation. You’d undoubtedly roll out the red carpet, welcoming them with open arms. Yet, when a potential business partner presents an opportunity to save your organization an equal amount, they might struggle to even secure a meeting with you. Why is that?

Now, let’s pause for a moment and ask ourselves: Considering the pressing financial challenges facing health systems today, can we really afford to overlook these critical opportunities any longer?

In this article, we uncover the reasons that meetings don’t happen and make a persuasive case for change. With substantial cuts looming from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), our current efforts to sustain financial viability will soon be overwhelmed. Alarmingly, the organization’s instinctive reactions serve as antibodies that reject the very changes necessary to ward off this threat. Lastly, we introduce a transformative model of health system-advisor partnerships based on trust, transparency, execution, and collaboration, focused on delivering results.

The Context: An Operating Margin Challenge, Ignited by the OBBBA

Picture your health system’s operating margin plummeting by an astounding 18 points. Even the healthiest organizations would struggle to cope, and many systems could collapse entirely.

Is this overly pessimistic? The highly respected Advisory Board estimates that margins could decline by 8 to 18 points by 2034 due to the OBBBA.

The actual effect on each system will vary based on size, geography, Medicaid exposure, and reliance on the 340B program, among other factors. Oliver Wyman’s Impact Calculator reveals stark disparities among health systems: Consider comparable systems in various states: a system with $4 billion in revenue, a 25% Medicaid mix, and zero 340B exposure in Florida, Michigan, and New York. Wyman’s model suggests the impact on margins varies considerably:

OBBBA Impact: Operating Margins

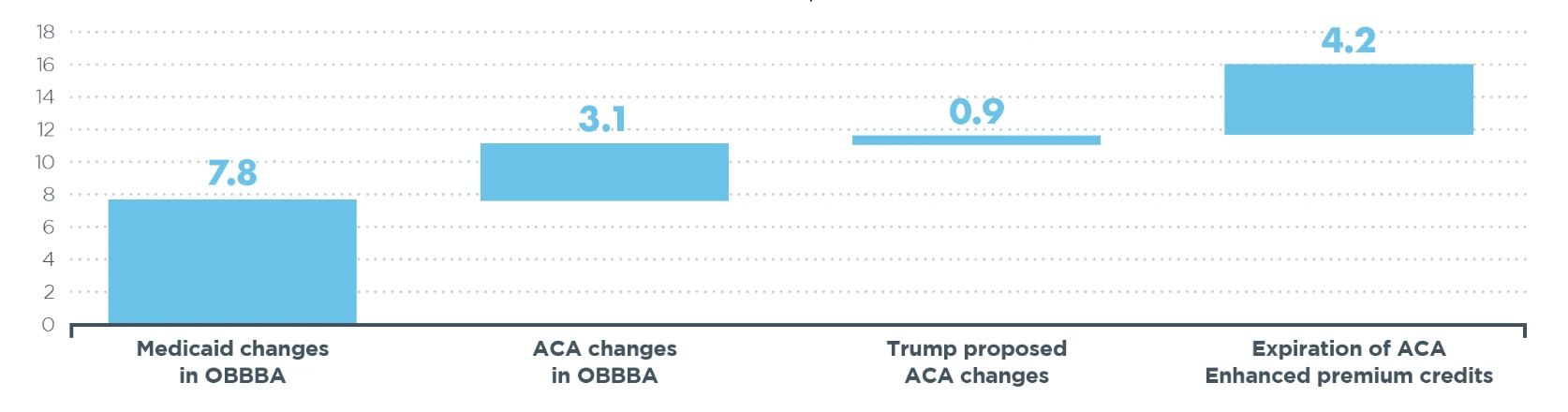

Much of this effect stems from an anticipated sharp decline in Medicaid enrollment and an increase in the number of uninsured patients. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that 16 million people will lose health coverage:

Expected Increase in Uninsured, per CBO, in Millions

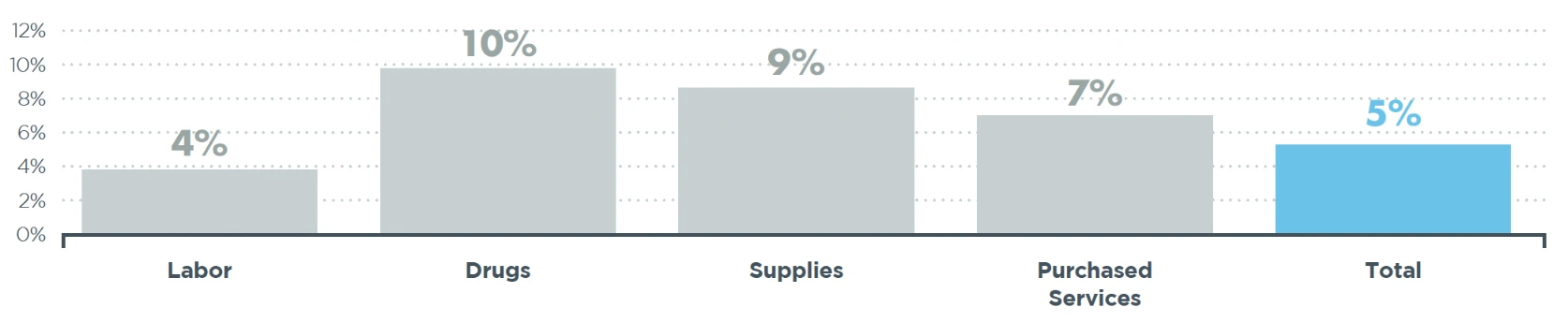

Few systems can absorb this hit: According to Strata, the median health system operating income was merely 1.2% in the first half of 2025. Meanwhile, expenses are outpacing inflation:

Year-over-Year Increase by Expense Category H1 2025, per Strata

The Advisory Board presents a more optimistic view of hospital margins, reporting a median margin of 5.9% in mid-2024. However, there is a shocking disparity between “healthy” and struggling systems. Systems at the 80th percentile report a 17% margin, while those at the 95th percentile boast a staggering 32% margin. In stark contrast, systems in the 20th percentile are experiencing losses approaching 20%.

The implications of the OBBBA are unmistakable: whether financially healthy today or not, few organizations can survive without fundamental changes in their services and operational structures. More sobering, these changes will not emerge without painstaking evaluation of the organization’s capacity for and approach to performance improvement. Achieving success will demand heightened agility, swift decision-making, a shift in managerial expectations, dismantling the mindset that clings to the status quo, and embracing the wealth of opportunities that external partners and advisors can provide.

The Dilemma: Rejecting Outside Ideas

The human body instinctively rejects foreign objects that threaten its stability and well-being. Organizations are no different, displaying a similar resistance to outside ideas and change. Just as stress accentuates the body’s resistance, financial threats embolden the organization’s defense mechanisms.

However, just as the human body can benefit from the right interventions, including vaccinations and organ transplants, organizations must learn to embrace new ideas and perspectives. Long-term survival depends on it.

What are the organizational antibodies that protect the organization from harm yet simultaneously hinder its ability to address potentially catastrophic threats, such as OBBBA? For this article’s purposes, we consider six factors:

1. Overwhelmed Management and Staff

In the post-pandemic era, healthcare systems are inundated with admissions, visits, procedures, tests, and other demands, straining their capacity. Staff shortages, particularly among clinical and technical positions, are rampant. Despite this, organizations undertake multiple, simultaneous improvement initiatives and ERP or EHR implementations. Managers are too burdened to consider new improvement opportunities, regardless of their potential benefits. Unfortunately, many of these time-consuming initiatives fail to yield significant results, leaving organizations ill-prepared for the looming financial crisis.

2. In-house Biases and Overestimations

Healthcare managers often harbor the belief that they can achieve everything better internally than anyone else could (despite having limited time). This mindset, lacking supporting evidence, contributes to fewer true partnerships, resistance to ideas, less outsourcing, and ultimately, lower performance compared to other industries.

3. Distrust of External Advisors

In folklore, few figures embody deception like the traveling salesman, the charismatic stranger with a trunk full of empty promises and miraculous cures. Although they may not bear inert colored water “potions” like their forebearers, today’s external advisors arrive equipped with flashy PowerPoint decks filled with promises. Even more troubling, they often charge excessive fees to assess whether their inflated promises have merit. Of course, not all external advisors reflect this caricature. Since distinguishing good from bad isn’t easy, defaulting to distrusting all of them becomes the norm.

4. Fallacy of Delegation

Health systems operate in a world of complexity, conflict, specialization, and unrelenting stress. Coping with these challenges, executives turn to subordinate managers to evaluate the numerous improvement opportunities that are flooding their desks. Now, imagine asking a student to invite a peer to grade their homework; this scenario begs for the student (manager) to defend their paper (operation) and dismiss the credibility of the peer (external advisor). Self-preservation can stifle the flow of valuable ideas and hinder progress. Instead, the organization needs the executive (or an enlightened manager) to be the “adult in the room”, who can rise above personal biases. A simple flip of the question from “should we?” to “why shouldn’t we?” melts away the prejudice and encourages action versus inertia.

5. Unhealthy Reliance on Committees

At a recent HFMA conference (an association of healthcare finance executives), a reporter interviewed me for a trade publication’s podcast. The reporter asked, “If you had five minutes with a healthcare CFO, what would you say to them?” I warned them that their organizations were ill-equipped to keep pace with the rapidly changing healthcare financial landscape. “When was the last time the organization faced a major problem…and you didn’t address it by organizing a committee?” When it takes weeks for the committee to convene, it’s already too late. Committees also represent vested interests. They excel at solving complex challenges when time permits and when incremental change will suffice. With tariffs, NIH funding cuts, and massive Medicaid reductions on the horizon, that is not the circumstance we face.

6. “We’re Different”

Why not simply wear a sign inviting your trading partners to charge you more than they charge someone else for the same thing? Healthcare managers often repeat this refrain, intending to establish their organization’s complexity and its standards of excellence. At worst, it serves to justify poor benchmark comparisons with other health systems and with companies outside of healthcare. In a not-so-subtle way, it signals to your supplier partners that premium prices would be acceptable. We have come to refer to this as the “wedding premium” that healthcare pays relative to its retail counterparts. It’s truly no different than the surcharge paid by the newlywed’s parents for the hall, flowers, and photographer when the vendors understand that it’s “only the best” for the happy new couple.

Healthcare organizations face significant internal obstacles that can hinder their ability to address critical threats. Overwhelmed management, inflated self-beliefs, distrust of external advisors, ineffective delegation, and an overreliance on committees all contribute to a stagnation that could jeopardize their survival. To thrive in an increasingly complex environment, organizations must recognize and address these barriers, fostering an open-minded and proactive culture that embraces external insights and agile decision-making.

Redefining the External Advisor Model

Securing meetings more consistently with health system executives to explore significant margin improvement opportunities may require a transformational shift in the client-advisor relationship. External advisors play a pivotal role in this shift by fostering trust and demonstrating genuine expertise. By embracing a new approach that prioritizes results, bespoke solutions, and an unwavering commitment, advisors can revolutionize their engagements and secure those all-important meetings.

Building blocks of this new approach include investment-based selling, an explicit shift from assessment and advice to execution, and trust-based fee structures.

Investment-Based Selling

Imagine the typical sales pitch: “We can save you $10M annually!” This confident boast, often based solely on past successes with other clients, can come across as superficial when not backed by thorough research and understanding of the current client’s unique context. Client managers bristle at the lack of rigor behind the pitch, setting up an adversarial relationship from the jump. Furthermore, as the work unfolds and the limited rigor becomes apparent, promised savings fall short, and finger-pointing begins to assign blame for the shortfall.

Now, picture a different scenario, one where the advisor chooses to “invest” in the client during the selling phase. By embedding a dedicated team within the client organization, advisors achieve several critical objectives.

- Crafting bespoke solutions: Instead of retro-fitting a solution that may have worked for another client, advisors craft a solution uniquely fitted to the specific challenges facing the current client.

- Establishing credibility: Working closely with key stakeholders builds trust and fosters a genuine understanding of each other’s capabilities.

- Enhancing viability: By collaborating this way, the viability of the proposed solution increases, as does the likelihood of a satisfactory result.

Think of this investment-based selling approach as akin to an auto manufacturer creating a prototype of a new car line. It’s a bold strategy that carries inherent risks for the advisor and requires significant resources upfront, with no assurance of a deal. However, when done well, it allows the advisor to sell the agreement based on a compelling, tangible solution that should already enjoy client commitment and sponsorship.

To win the business with this investment-based approach, the advisor faces two critical hurdles:

1. Proving value: The advisor must use the prototype to demonstrate that the proposed value is not just theoretical but entirely achievable.

2. Justifying engagement: It is essential for the advisor to convincingly articulate why the client needs the advisor’s involvement to achieve the result, whether due to specialized knowledge, expertise, access to benchmarks, or simply the resources required to complete the work efficiently.

If the advisor cannot deliver on both, it raises the question: Did they deserve to be hired in the first place?

Shift from Assessment and Analysis to Execution

Faced with a challenging future, health systems should demand a fundamental shift in the delivery of advisory services. Gone are the days of exorbitant fees for lengthy assessments and fancy slide decks, particularly when the advisor should have completed the work during the sales process. Clients crave action and real, tangible results.

Advisors must evolve to a model that rewards execution over recommendations. Health systems are wary of analyses that fail to translate into actionable solutions. Moreover, they bristle at paying someone to tell them what they already know, only to leave the implementation to internal staff.

Imagine a new model where advisors function as true extensions of the internal team. Clients deserve advisors who are seasoned professionals who have walked in their shoes. It’s time to say goodbye to the generalists and those fresh out of school, and to embrace seasoned experts who can carry the load from concept to execution.

Trust-Based Fee Structure

We seem to love risk-based deals…until we don’t. Aligning the advisor’s fees with the risk of delivering results ensures that the parties’ incentives are aligned and that the client realizes a return on investment (ROI). Time after time, however, we have witnessed these arrangements devolve into disagreements around scope and who deserves credit for the results. Trust dissipates, and the client typically pays more than necessary for the results achieved. It is certainly not a recipe for a collaborative teaming environment.

On the flip side, a pure fee-based arrangement cannot provide the client with the assurance of even a minimally acceptable ROI. Nothing in the deal holds the advisor’s “feet to the fire.”

Imagine a model that protects the client on the downside, with a minimally acceptable ROI, but fixes the upside payment obligation. Even better, fix the fee at a fair rate for the effort exerted by the advisor. This model avoids most of the bickering over scope and credit assignments, enabling better collaboration and trust among the parties. Keys to success in this model are 1) completing a prototype or solution during the sales process that is sufficient to establish the minimum, likely, and best case results, 2) crafting a resource model needed to deliver within this expected range of results, and 3) committing to a fee model with an expected fixed fee to deliver results within this range, complemented with a “no embarrassment” clause that claws back fees in the (hopefully, unlikely) event that results fall below the minimum expected level and the minimally acceptable ROI.